High-profile figures like Senator Rick Scott, former Representative Michelle Bachmann, and former Trump strategist Steve Bannon have made a startling claim about a proposal the United States sent to the World Health Organization. That proposal, which some Republicans call a threat to American sovereignty, outlines several line-item amendments to the International Health Regulations (IHR) that govern international emergencies. The purpose of those changes is to allow nations to better deal with situations like the COVID-19 pandemic.

“The biggest global power grab that we have ever seen in our lifetimes,” is how former Rep. Michelle Bachmann described the amendments in an interview with Steve Bannon. “If this goes through, nothing else matters.”

"This is the BIGGEST GLOBAL POWER GRAB that we have seen in our lifetimes."

🆘🆘🆘

Upcoming vote in Geneva over Biden administration’s amendments that cede US sovereignty to the WHO over ANYTHING they deem a healthcare emergency.@LeaderMcConnell @GOPLeader @Jim_Jordan pic.twitter.com/N0AWwgTyop— NEWSNANCY (@NewsNancy9) May 10, 2022

A claim like that warrants a careful examination of the document — especially when other prominent Republicans have raised vague concerns like Senator Rick Scott.

The @WHO has served as a puppet for the Chinese Communist Party & helped Communist China cover up info on COVID-19. The Biden admin must NOT give this sham of a health agency national sovereignty over the U.S. & control over Americans' lives & health. https://t.co/mt4NtgOyxx

— Rick Scott (@SenRickScott) May 14, 2022

Other countries, such as the United Kingdom, have suggested that any changes should be legally binding. The United States has not taken that position and instead opts for moderate modifications to the language. At times, these changes are purely semantic and constitute an attempt to stress the urgency of international health emergencies. However, the majority of the changes set a concrete timeline for WHO and its member states to adhere to when it comes to disclosing and releasing information in the case of an international health emergency.

In any case, WHO is not granted power within the territory of its member states — it cannot force states to take action or overrule their decisions to not act in a certain way. As it already could, it can still offer recommendations to those states and disclose information to other states about the potential for an international health emergency.

These proposals have been characterized as handing United States’ sovereignty over to the “CCP-controlled” WHO. However, it’s possible that, if implemented years ago, the world would have been notified about the potential for a COVID-19 pandemic more quickly. For instance, China would have been obligated to explain why they were quarantining certain planes, and WHO would have been permitted to declare a potential threat. Issues like whether travel restrictions were fair to implement would have been much clearer as well.

So what exactly do the amendments say, and what are they trying to address and prevent? The proposed amendments change 13 articles, and each is discussed in depth below.

Article 5: Under IHR, each state party is expected to monitor their territories for public health emergencies and notify the World Health Organization. In 2005, when these regulations were adopted, Article 5 required states to implement programs that, if such institutions did not already exist, would enable the government to detect public health emergencies such as an Ebola outbreak.

Proposed Changes/Additions: If a state struggles to monitor for infectious diseases and requests assistance, WHO is obligated to provide support to that state. If regional or global risks arise with an unknown origin or cause, WHO is compelled to inform state parties about their risk assessment findings.

Article 6: Signatories to the IHR agreement are obligated to notify WHO of an adverse public health event that may pose an international threat within 24 hours after that threat is first assessed and describe any actions taken to mitigate that threat. If the public health risk involved something that would concern the International Atomic Energy Agency — such as a meltdown — WHO is obligated to inform that agency.

The national agency responsible for communicating with WHO must then keep the international community apprised of developments such as lab results, severity, and actions taken to mitigate the risks.

Proposed Changes/Additions: The assessment must be conducted within 48 hours of the state agency obtaining the “relevant information” concerning the event. In other words, the communication timeline from when a national agency learns of the event to when the international community is notified will be expedited. Additionally, if other international agencies such as the Food and Agriculture Organization or the World Organization for Animal Health would benefit from this information — in the case of bird flu, for example — WHO would be obligated to inform them.

When informing WHO about ongoing developments, any genetic sequence data concerning the disease should be shared and the state party should use “the most efficient means of communication available.”

Article 9: WHO may analyze reports from sources other than the state party’s designated point of contact and must inform the state where that event is allegedly occurring of their findings. However, they are not required to obtain the consent of that nation. The source of the allegations must be made public unless confidentiality is duly justified, and WHO must consult with that state before taking any action.

Proposed Changes/Additions: WHO is not required to consult with the state party before declaring a public health risk to the international community. But, per Article 10 (below), they are still obligated to consult with that nation, verify the public health risks, and fully inform the state about the allegations they seek to verify. The consultation and information sharing must occur within 24 hours of obtaining the report on the alleged health risks.

Article 10: WHO must request that the state party verify or disprove the allegations of an event that may constitute a public health emergency of international concern and provide information on the reports it seeks to verify. State parties are obligated to reply within 24 hours and provide any relevant public health information concerning the alleged health emergency of international concern.

WHO must also offer to provide technical assistance to the state party in question. If the public health risk is verified, and of particular concern to the international community, and the state party has refused to collaborate and inform WHO, the organization is obligated to share that information with its other members.

Proposed Changes/Additions: WHO must contact the state mentioned in the third-party report and offer assistance within 24 hours. The state party then has 24 hours to respond and request additional information from WHO and WHO must furnish that information within 24 hours thereafter. If the State Party does not accept WHO’s collaboration at this point, WHO is obligated to immediately inform other state parties if there is a public health risk.

Article 11: This article lays out the various reasons that WHO might inform parties of a situation unfolding in another nation. Those reasons include the event is already a public health emergency, evidence of international spread exists, control measures have failed or are likely to fail, the state party does not have the resources to prevent further spread, the nature of the invent involves the movement of travellers, cargo, or parcels that will require the international community’s cooperation to mitigate. WHO must first consult with the state party that the incident has taken place in.

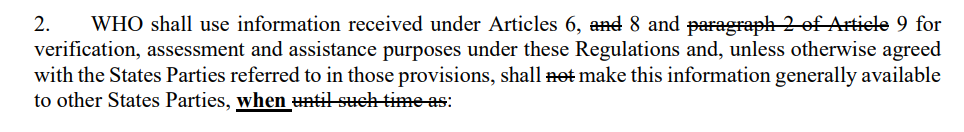

Proposed Changes/Additions: WHO is now obligated to issue an annual report on any instances of information sharing in which they have been involved. Critics have argued that paragraphs 2 and 3 of this article constitute a breach of state sovereignty — pointing out that WHO is no longer obligated to “consult” with the state on “the intent to make information available to other parties” but must merely “inform” the state of their intent to do so. Some critics appear to be confused about the purpose of paragraph 2 as well, but the changes in that paragraph are entirely superficial and semantic:

The striking of “not” and “until such time as” might appear, at first glance, to substantially alter the meaning of this paragraph.

A closer reading quickly reveals this to not be the case. In both instances, the language asserts a right by WHO to use the information (“shall use”) and an obligation to keep that information confidential (“unless otherwise agreed”) until a certain trigger (“shall not”/”shall”) releases them from that obligation (“until such time as”/”when”).

Article 12: This article lays out the process that the Director-General must follow before declaring a public health emergency exists at the international level. The preliminary determination, according to the original text of the article, will be discussed with the state party wherein the event occurs. If the state party and the Director-General believe that the event constitutes a public health emergency, the Emergency Committee will be summoned to discuss temporary recommendations.

Proposed Changes/Additions: The Director-General will now notify all other state parties that there is a potential public health emergency and, regardless of whether the state party agrees, consult with the Emergency Committee to determine if any recommendations should be issued.

Article 13: Upon the request of the state party, WHO will offer assistance in dealing with the public health emergency. WHO is empowered, but not obligated, to offer financial assistance, risk assessment, and other technical aid to the state party dealing with the situation.

Proposed Changes/Additions: WHO is obligated to offer assistance, whether requested by the state or not. If the state party rejects the offer of assistance, they must explain their rationale and WHO will share that response to the other state parties. State parties should grant “reasonable” access to WHO to the extent that their national laws allow and for the purposes of assessing the situation. If the state party denies access to WHO they must inform the organization of their reasoning.

Article 15: This article deals with temporary recommendations that WHO might issue to states in order to mitigate public health concerns.

Proposed Changes/Additions: In addition to recommendations on travel, trade, and other movements of goods and people, the proposed amendments add that WHO may suggest the deployment of “expert teams.”

Article 18: This section has been altered only to advise state parties to take care in imposing restrictions that might impact the supply chains of medical products or the travel of health care workers. To that end, WHO is able to discuss such matters with the International Civil Aviation Organization, the International Maritime Organization, and the World Trade Organization.

Article 48: This article describes the composition of the aforementioned Emergency Committee, which is selected by the Direct0r-General of WHO. At least one member of the Emergency Committee should be nominated by the State Party within whose territory the event arises.

Proposed Changes/Additions: State parties that border the state where the event arises should have representation on the committee and, when appropriate, regional directors from the state where the event arises should be represented as well.

Article 49 has been altered to mandate that dissenting opinions on the Emergency Committee have their place in the Committee’s report.

New Chapter – The Compliance Committee: This proposed committee will monitor whether the state parties have adhered to the timeline restrictions proposed in earlier chapters, make recommendations to state parties and, with the consent of the state party, conduct information gathering on its territory. It would be comprised of representatives from each region and members would serve four-year terms.