After the men used a pulley to lower three large drums of dead fish onto the stern of the lobster boat, the Captain steered through the dark toward the lighthouse, and Sam, the sternman, said, “There’s no turning back now.”

The boat was 45ft long. It growled like a big truck. The old wooden dock in Portland, ME disappeared behind us.

Sam’s been the sternman for Captain Mike going on eleven years. The Captain’s been at it for 48.

According to Maine law, it is illegal to haul traps “During the period ½ hour after sunset until ½ hour before sunrise from June 1st to September 30th.” We moved 20 knots through the water on our way to the first set of traps. Commercial lobstermen in Maine are allowed to have up to 800 traps out at once. Captain Mike and Sam have twenty traps connected to each of their buoys.

The boat had an open stern. The Atlantic was right at our feet. Should you slip, the water will eat you. I held onto the edge of one of the drums of dead fish for balance.

We put on our bright orange waders, waterproof boots, and thick blue gloves. The gloves would offer some protection from the lobster claws.

I had heard a story about Captain Mike a few days earlier. A woman was recently on the boat and her iPhone fell overboard. She hadn’t realized it was gone until after she lost it, but they had a pretty good idea where it fell into the ocean. They got a hold of a scuba diver and brought the diver to where they believed the iPhone dropped. Captain Mike tossed a hammer into the ocean to show the diver where he believed it would be. When the diver came back up to the surface, he had the phone and the hammer, and he said the hammer was right on top of the phone.

This could just be a fisherman’s exaggeration, but these guys know the ocean the way a farmer knows his land. As we made our way towards the first traps, I asked Sam how he’d fare out here without the GPS in the cabin.

“I can navigate these waters with my eyes closed,” he said.

*

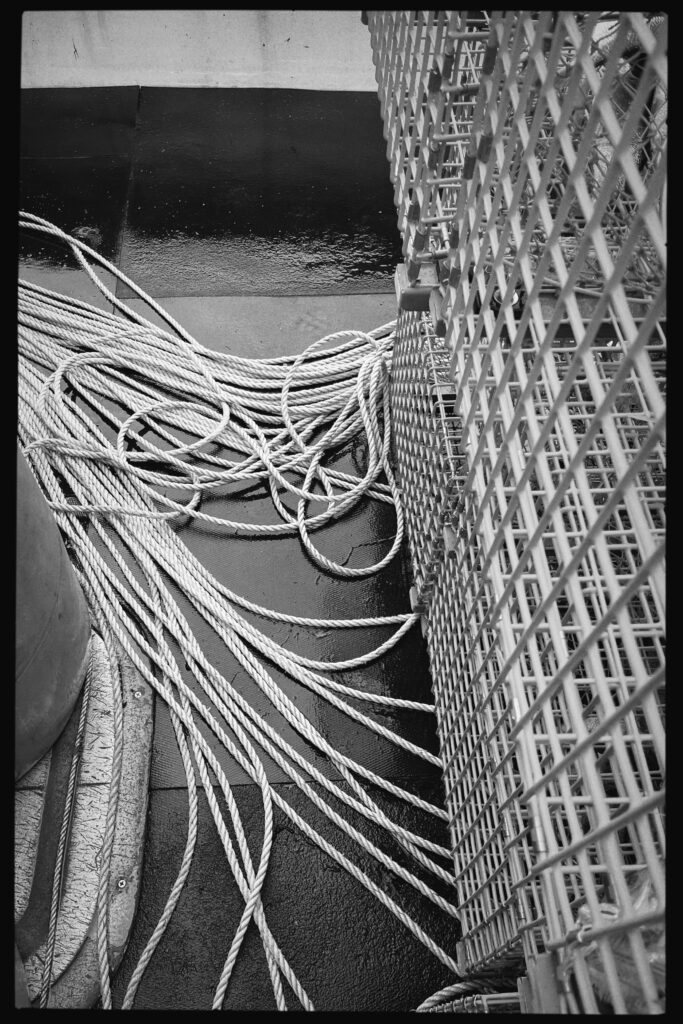

This is the process for hauling the traps: The Captain steers the boat to his buoy. He takes a hook attached to a long pole and grabs the rope attached to the buoy. He pulls the buoy onto the boat and runs the rope through a mechanized pulley system. He switches on the pulley, and it automatically starts to hoist in the rope. Sam walks the buoy to the back of the stern and lays it down by the large metal tank filled with ocean water where I will drop the day’s catch. As the rope begins to pile up at the Captain’s feet, we look overboard waiting for the first trap to emerge. The traps are metal cages that have been filled with bait—typically dead, salted pogies AKA menhaden. On the ocean floor, the lobsters will crawl in through the trapdoor to eat the fish and typically have trouble finding their way back out.

The Captain reaches down to pull the heavy trap out of the water and places it on the gunwale. He and Sam get to work. As the Captain plucks the lobsters from the cage to inspect for size, Sam is driving a small iron spear through the gills of four pogies at once and threading it through a thin rope into the trap and shutting the cage door. They toss the lobsters that are too small back into the water. The Captain places the lawfully sized lobsters in a basket behind him. He uses a gauge to measure each lobster.

According to Maine’s Marina Resources:

A legal lobster in the State of Maine has a carapace or body shell length that measures between 3 1 /4. inches and 5 inches. The measurement is made between the extreme rear of the eye socket to the end of the carapace…

The next traps emerged. It is constant and grueling work. Sam stacked all twenty traps on the stern.

We caught a “breeder” in one of the traps. These are legally protected and must be tossed back into the water to help conserve the population. Breeders can carry up to 100,000 eggs, depending on the size. The eggs are tiny black spots, sometimes referred to as “berries.” They are stuck to the swimmerets under the tail. The tail must be clipped in a V-shape by the lobsterman before tossing back out so future lobstermen know this is a breeder should there be no eggs when it wanders into a trap again.

Sam handed me the breeder to look at before we dropped her back into the water. Her claws were massive.

“She’ll chop your hand off,” he said.

The whole time we’d been hauling traps, the Captain had Ozzy’s Boneyard Sirius Radio station blasting on the boat speakers. They say lobsters can detect low-frequency sounds. If that’s the case then the first noises they heard as they joined us were Black Sabbath, Guns N Roses, and the Misfits.

The stern was slick after the first haul. As the Captain throttled off towards the next buoy, everything loose shifted backward. Unless you have the sea legs of the Captain or the Sternman, you hold onto the drum of dead fish or the side of the boat so you don’t slide down off the open stern into the ocean.

I asked Sam if anyone on this boat had ever fallen overboard.

“Just me,” he said. “We had 100 traps on the boat.”

Each stack was six traps high (unlike today, where it was four to a stack.) The first two traps slid back into the ocean with no problem, but then something happened where the next two went out simultaneously. The rope pulled the whole next stack down and knocked him so hard in the hip that he got thrown into the water. He said he’s lucky the traps didn’t get him in the ribs. He caught a nasty bruise.

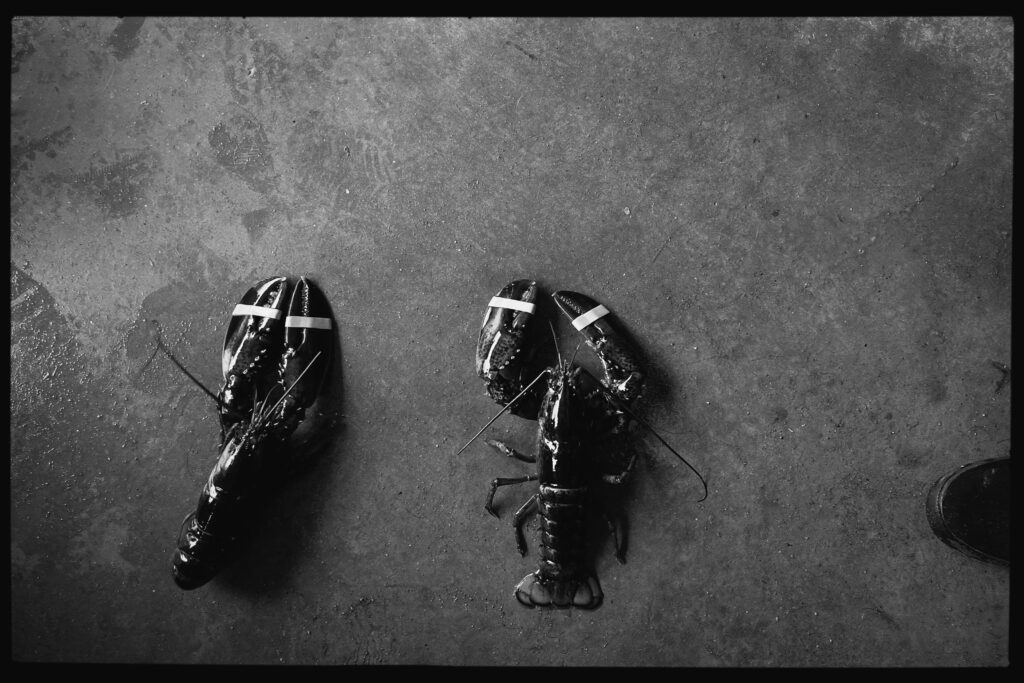

Sam gave me the basket of lobsters to band their claws shut. There was a distinct and overwhelming stench of dead fish and live lobsters—that, with the salt air and the swaying of the boat, makes seasickness understandable. I was thankful I kept my wits about me.

Some of the day’s catch were missing limbs, but lobsters are capable of regenerating them. On a few, I could see where new claws were beginning to bud.

To band a lobster, it’s easiest to hold the claws over the lobster’s head as its long legs and tail try to push me away.

When I pull some from the basket, they are clamped to one another. Lobsters are also cannibals, especially in captivity. So, the rubber bands protect us, but they also protect them from each other.

Once each lobster’s claws were banded shut, I dropped them in the tank. The tank held a few hundred gallons of ocean water. As the boat picked up speed, the water spilled out and you felt the cold even through the thick boots.

Sam pushed the traps off the stern and back into the ocean. They went down with little help. Sam was careful about the placement of everyone’s feet so no one got yanked into the ocean. The rope moved fast from the stern into the ocean as the traps started to sink. Once all twenty were back on the ocean floor, all that’s left was the buoy.

“How much has politics gotten in the way of lobstering?” I asked the Captain.

“All this whale shit is the problem,” he said.

“What’s wrong with the whales?” I asked.

“They wanted to pass a law restricting vertical lines in the water. How are you supposed to haul a trap out without vertical lines?”

He’s referring to the ropes. There were politicians saying that the ropes on traps were catching whales.

They eventually scrapped the policy idea.

“I can’t catch a fucking whale,” the Captain said.

The more traps the Captain opened, the more fish bones started to litter the boat.

We had about 380 more traps to haul in six hours.

There was a point in the day when the fog had become so thick you couldn’t see land. The water constantly rocked the boat. There have been days when these men have worked against ten-foot waves hitting the boat every twelve seconds.

*

We dropped some traps in the water somewhere off Peaks Island—an island filled with mansions with oceanfront property. As the large windows and manicured lawns watched us return to shore, Sam spilled the blood and guts from the empty bait drums back into the water.

Kids waved at us from their tables in the restaurants along the pier.

It was high tide, and we weighed the bugs on the dock. Sam and the Captain divvied up the day’s catch, knowing certain buyers wanted specific amounts.

“Was this a good day or a bad day?” I asked the Captain.

“A shit day!” Sam said.

“Not terrible,” the Captain said, looking at the whole of the catch for the first time. “It’s a lot of bugs,” he said.

There were already people waiting to buy lobsters. One young woman showed up with a cooler. When she saw the Captain, she yelled to her mother to come and say hello. The mother said she was glad to see the Captain was out and about—it turns out he recently had a quadruple bypass.

*

On the way home, near Sebago Lake, we pulled into Pat’s Pizza. This was Sam’s routine. We took a seat at a table with two older men. They’re talking about the preference of a lake over the ocean. One look at Sam’s white shirt covered in blood and guts affirmed their love of the lake. The entire place could smell us—salt, dead fish, lobster.

The bartender placed a pint on the table and dropped a five-gallon bucket of ice at Sam’s feet. He took a swig, got up, and took the ice to dump into the cooler of lobsters in the bed of his truck.

“I’ve gone 55 days without a day off,” Sam said.

In the winter, the days will be longer. The lobsters migrate about an hour further from shore.

“On the days we don’t fish,” Sam said. “I sell lobsters.”

He runs his own lobster pound—The Trailside Lobster Pound. He says people will drive past three other lobster pounds just to get to his. He thinks it’s because he is selling and cooking lobsters caught that day or the day earlier. They’re all fresh, and he steams them in seawater. Many people in Maine believe cooking the bugs in the saltwater makes all the difference.

“I’m handpicking these things,” he said.

At the pound, he keeps the lobsters in a two-tiered red tank that pumps through ocean water.

He doesn’t mind the early days. He can be back on land anywhere between 11 a.m. and 1 p.m. Pat’s Pizza offers him a brief moment to decompress. At the table, my legs still felt like they were on the boat—trying to maintain balance.

Sam’s waiting to get his lobster license from the state. There’s a long waitlist. He’s been on it since 2015 or 2016. A lady with Maine’s Marine Resources once called to ask if he was still interested in obtaining a license. She told him lots of people on the list had died or were too old and didn’t care to fish anymore. So, he moved up the list.

There are ocean men, and there are lake men. The two old men at our table told us they prefer the lake even though it can have rough days, too. Plus, there are eels, undercover game wardens, and it can be choppy out there, too in bad weather. But both waters are predictable to the men who navigate them daily.

When we were on the Atlantic that morning, consumed by fog, pulling “bugs” from the water, Sam and the Captain seemed more like astronauts than fishermen. It’s an abyss that far out. And the lobsters, these giant reddish, brownish, blueish, yellowish marbled creatures with powerful claws and exoskeletons, look like they’re on the wrong planet.

When I was banding claws, their eyes and antennae moved in tandem. They don’t have brains, but they looked like they were trying to communicate. They don’t have great eyesight either. If anything, I was only a shadow tightly holding them. At that distance from shore, neither of us felt like we were on Earth.

Sam will have a beer or two after a day of fishing and then head over to the pound. There could be 40 orders lined up waiting for bugs to be steamed. And the price of lobster fluctuates like the price of gold.

He took another swig of beer and said, “I just need an hour to forget about lobsters.”