The most prominent anarchist in the United States — if not the world — is offering a radical new cure for what ails you. It may be hard to swallow, but it has the potential to reverse your bleak outlook on the future.

After years of dishing out red pills on Twitter and YouTube, Michael Malice is now urging anyone sickened by the state of the country to take The White Pill. His new book, subtitled “A Tale of Good and Evil,” transforms the catalogue of atrocities that occurred within the Union of Soviet Republics during the 20th century into a kind of gothic body horror page-turner. However much one may or may not know about the unthinkable evils that befell millions after the Russian Revolution, he presents them through a fresh lens.

“For this [book], I think I was targeting Americans in their innocence,” Malice told Timcast in an interview. “Those who have some idea of what the evils of government are like don’t have a good understanding of what that entails, day to day, minute to minute. I also wanted to express to people, with receipts, why I am so hopeful for the future of this country.”

For those unfamiliar, there are essentially three “pills” available to those who are “blue-pilled,” a term which Malice applies to people who “have been trained to believe that anything that contradicts the corporate press’ narrative is thereby a conspiracy theory.”

The red pill offers an alternative to this malignant state of mind; an opportunity to wake up to the reality of the Matrix rather than roll over and go back to sleep.

“[It’s] the concept that what is presented as truth by the corporate press is in fact a carefully constructed narrative designed to keep some very unpleasant people in power,” Malice explained to author Douglas Murray on an Oct. 28, 2020 episode of the “YOUR WELCOME” podcast. “And that they do this not hypocritically, accidentally, [they do it] intentionally and by design.”

Malice cautions people to “take one red pill, not the whole bottle” lest one overdoses to the point where they become “black-pilled” and “abandon all hope.” The person who takes the black pill subscribes to the belief that “there’s no way the West can be saved given these current trajectories,” Malice told Murray.

But there is an antidote: the white pill, which Malice said offers hope that “the good guys will win, and even if we don’t win we sure better go down fighting. And the concept that the villains, who are our contemporaries, are impossible to defeat is an absurdity.”

This belief forms the basis for his new book, which, on its surface, offers a despair-inducing reading experience. The White Pill is a staggering feat of historical scholarship that adds vivid detail to the widescale human suffering that occurred within what Malice refers to as “the largest prison that the world had ever seen.” But by painting such a vivid portrait of hell, he offers a promise for optimism encased in a provocation. Malice’s white pill suggests that (a) no matter how many problems we have in the U.S., it doesn’t compare to life under Stalin, and (b) even though it seemed as if the USSR was a permanent regime, it ultimately “vanished from the face of the earth” in the same way that Ernest Hemingway described how bankruptcy happens — “gradually and then suddenly.”

In some sense, this is next-level trolling from one of the greatest trolls alive. His book plunges you into the pure terror of a hellscape unimaginable to the modern Western mind in an attempt to put our national struggles into a broader, more meaningful context. This might come as a shock to most fellow countrymen who pick up and ingest The White Pill, but that might be part of Malice’s motive — to throttle you, to shake you till your teeth rattle, to remind you of the bloodshed and mania of historical evil that you either forgot about or never truly understood.

Then, mastermind troll that he is, Malice says, in effect, “See? You don’t have it so bad. Plus, the people who run this country are so unimpressive they’re kind of destined to fail.”

But that’s me paraphrasing one of the great disruptors of our time when he should speak for himself:

I think the premise of The White Pill and my work in general is far more broader than merely the evils of government. The willingness if not downright eagerness of average people to rat out their neighbors to the authorities is another evil we have all witnessed, as well as the ease with which the media can create an outgroup that blue-pilled people can be easily driven to despise to the point of wishing them dead for no coherent reason whatsoever. That said, I was driven to write the book partly because so many people I communicated with thought that it’s game over, that we cannot win against such insurmountable odds — something I found to be completely incorrect.

‘The Willy Wonka of Politics’ vs. Midwits and The Enemy Class

One pauses before describing Michael Malice. He is entirely unlike anyone you’ve ever encountered. He’s ruthless but jubilant, acerbic but lighthearted, hostile but hospitable, savage but kind. During interviews, he can shift from cackling sprite to dead serious. It’s not uncommon for him to interrupt someone’s laughter during a broadcast by saying, “I’m not joking.”

To be fair, it’s hard to tell.

“He’s not the kind of person who can come out and say something as is,” Michael Fazio, who worked with Malice on his book Concierge Confidential, told the Observer in 2013. “I think his gift is to twist it all up, and get you confused, but ultimately get you to the right place.”

He’s like a punk rock Pauline Kael with Ayn Rand’s penchant for asking the right questions and Emma Goldman’s anarchistic conviction. Though small in stature, his presence in the digital world summons Whitman’s declaration: he is large, he contains multitudes.

Though he is perhaps first and foremost an author, Malice is also an ingenious troublemaker on Twitter, where his over half a million followers can relish his pithy and devastating interactions with users who don’t possess a modicum of his intelligence. It typically only takes one reply from Malice to cause someone to become apoplectic before ultimately surrendering in shame.

His timeline is punctuated with quote tweet retorts where he writes:

weird, he blocked me by mistake

— Michael Malice (@michaelmalice) June 4, 2022

They deleted their account

— Michael Malice (@michaelmalice) August 21, 2022

weird he blocked me and locked his account

— Michael Malice (@michaelmalice) December 14, 2022

he blocked me and locked his account

he asked “explain drag queens” and i replied— Michael Malice (@michaelmalice) March 1, 2021

and deleted it entirely

— Michael Malice (@michaelmalice) August 10, 2021

Malice takes immense pleasure in lashing out at those he deems to be deserving of ridicule. Take, for example, his ruthless Twitter rampage against Alec Baldwin after the actor shot and killed the cinematographer on his film set in October 2021.

I wonder when Alec Baldwin will resume shooting

— Michael Malice (@michaelmalice) October 23, 2021

Alec Baldwin gives new meaning to the term executive producer.

— Michael Malice (@michaelmalice) October 30, 2021

Alec Baldwin is so good at getting away with killing women that they’ve made him an honorary member of the Taliban

— Michael Malice (@michaelmalice) October 22, 2021

The insane part is that Alec Baldwin clearly is a very very good shot

— Michael Malice (@michaelmalice) October 22, 2021

Between his wife and his murdering Im pretty sure Alec Baldwin just got into MS-13

— Michael Malice (@michaelmalice) October 23, 2021

I believe two things are true

1) Alec Baldwin feels horrible about what happened on his set

B) Alec Baldwin feels livid that his feeling bad isn’t enough for some people— Michael Malice (@michaelmalice) October 31, 2021

And months later, in July 2022, following the assassination of Japan’s former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, he tweeted:

i didnt realize Alec Baldwin was in Japan

— Michael Malice (@michaelmalice) July 8, 2022

In Malice’s view, Baldwin is a member of the Enemy Class.

“I think murderers should be scorned, especially when they portray themselves as the victim,” he told me.

Malice hosts a popular YouTube program and podcast called “YOUR WELCOME,” where his guests include Jimmy Dore, Alex Jones, Ann Coulter, Eric July, Blaire White, Glenn Greenwald, Jesse Lee Peterson, and show favorite Dave Smith. The show’s title is an incitement against so-called “midwits” who too eagerly take the bait and accuse him of not knowing how grammar works.

“One of the best things about not being behind a paywall is that every episode brings new midwits ‘correcting’ the show title,” Malice said in 2018.

Pretty sure I know how to spell the name of my show https://t.co/Re8BCsnGET

— Michael Malice (@michaelmalice) August 8, 2021

In his 2019 book The New Right: A Journey to the Fringe of American Politics, Malice explains the phenomenon of the midwit, a term coined by Alt-Right writer Vox Day:

It is true that poor spelling correlates with lower intelligence and lower education level especially. But the inverse is not true at all: having good spelling does not make one particularly bright. Knowing the distinction between “your” and “you’re” is possessing the knowledge of a second grader, yet a mid-wit takes this as evidence of their own intelligence if not genius.

So when he kicks off each episode by saying, “Good afternoon, Michael Malice here, let that be your welcome for the next hour,” he’s further antagonizing the midwits.

Last year, he added underwear model to his resume — “one of the greatest accomplishments of my life,” he said during a recent podcast — after collaboratively designing a limited edition pair of briefs for Sheath Underwear. (The most popular sizes are already sold out.)

If you need protection–and let’s face it, with a murderous Alec Baldwin on the loose, we all do–Sheath Underwear is the underwear for you

Promo code Malice gets you 20% off and might just save your lifehttps://t.co/tIEvwNep3E pic.twitter.com/68ZhiTLWzQ— Michael Malice (@michaelmalice) October 22, 2021

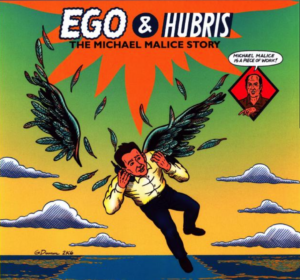

After the legendary underground comic book writer Harvey Pekar, an infamous crank in his own right, met Malice, he called him “one of the most puzzling twenty-first century Americans I have ever met” — an observation that no doubt led Pekar to write 2006’s non-fiction comic book Ego & Hubris: The Michael Malice Story. (Anyone interested in finding a new hardcover copy of the comic can nab one on Amazon for about $600, though you can find copies as low as $150.)

Though Malice still puzzles, he also offers a profoundly lucid point-of-view amid confusing times. As an anarchist, he sees piercingly through the wispy nonsense peddled by the Establishment. One delivery mechanism he uses to share his perspective involves crystaline aphorisms that rival Nietzsche in clarity and precision. For example, he often reminds us “there is no law so obscene that the police would not be willing to enforce it, up to and including the mass execution of innocent children.” He also shuts down users by saying, “I don’t want to change your mind or argue with you, but I don’t want to share a country with you either.”

“Years ago, I called Michael Malice ‘the Willy Wonka of politics’ and he lives up to that moniker every day,” Dave Rubin, host of The Rubin Report, told Timcast. “He’s quirky, irreverent, curious, brilliant, subversive and perhaps most interestingly, very kind, at the exact same time.”

Rubin added: “He’s a fantastic fighter in the culture wars because he’s impossible to define. He shocks people through his humor, wit and trolling, but little do they know that the troll they’re trying to silence is red-pilling them in real time.”

The Making of an Anarchist

Those who encounter Malice through his vicious tweets or his hours-long appearances on the Lex Fridman Podcast and The Joe Rogan Experience aren’t given much insight into the crucible from whence he sprang. Though he has authored or co-authored about a dozen books, his background is never presented front and center — with one notable exception: Pekar’s Ego & Hubris.

Though Pekar is listed as the author of the comic, Malice’s distinct point-of-view drives the storytelling. He claims he wasn’t credited as a co-author because, at the time, he wasn’t a “brand name, which I think is the correct decision.” According to an interview published on the Random House website, Pekar’s version of Malice’s story was based on a “huge document” he mailed to the comic book writer.

“I think the vast majority of it is verbatim from my text, something Harvey stressed he was very keen on,” Malice said at the time.

He told me that Ego & Hubris might be the book he’s most fond of: “Having a book written about you before you’re 30, and by a comic book legend, is surreal even for me.”

Portion of the cover of Harvey Pekar’s comic book “Ego & Hubris: The Michael Malice Story.” Ballantine Books, 2006.

The following details are gathered from his collaboration with Pekar and Gary Dumm, who’s credited with the art.

The overall arch of the narrative describes an extremely high-IQ individual who is constantly butting up against low-IQ NPCs at a time that preceded the notion of non-player characters. The protagonist is a maverick who has no tolerance for those who are intellectually beneath him but always eager to embark on a power trip.

When I asked Malice — who doesn’t believe in voting and has referred to democracy as “an obscenity that is contrary to freedom” — how he would advise the average person to remain aware of and guard against the evils of government, he replied: “I don’t believe in advising people, especially average people.”

He continued:

But to answer your question another way, I was raised to always be aware of who had power over you and to be mindful that they would often relish in leveraging that power in vindictive ways or to simply exercise a flex. Americans don’t think that way. They think that if you have a problem at work, the best approach is to sit down and have an honest conversation about it. This from my perspective is often the wrong approach if not completely insane.

Though Malice doesn’t claim to have had an abusive or horrible childhood, he does say it wasn’t a childhood suited for a human being. He was born July 12, 1976 in Lviv when it was in the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic. In the years following his family’s immigration to the Bensonhurst neighborhood of Brooklyn at age two, he largely seems to have lived in a world of his own. He watched a lot of TV, read voraciously, and collected trading cards with animals that he spent time organizing and re-organizing.

this is the airport from which my family and i escaped the Soviet Union in 1978 https://t.co/csI8Hak792

— Michael Malice (@michaelmalice) March 18, 2022

His mother, whom he described as “dumb” and “beautiful,” left him feeling neglected and disliked. He has distinct memories of her telling him that he was a bad person, he had no friends, and she wouldn’t be friends with him if she were his age. He recalls being dragged along with her on shopping trips that seemed to last an eternity. He despised these endless trips and his contempt for authority carried on into grade school, where he encountered teachers that failed to appreciate his imagination.

Malice said his father was very smart in some ways, but he also describes him as someone who had no respect for anyone else’s values or privacy. Aside from stealing money from his wife’s purse, his dad would interrogate his son about the contents of his diary. His father would regularly forage through young Malice’s belongings and throw away anything that his father deemed garbage. If his son complained, his father would shrug and say, “It’s gone now.”

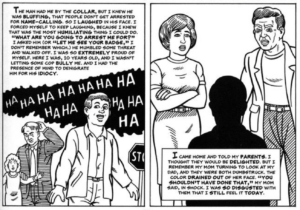

An early example of Malice’s intolerance for phony authority occurred in fifth grade. A name-calling tiff with a classmate escalated to the point where the girl said she would tell her dad, who was a cop. The girl’s father confronted Malice after school and said the boy shouldn’t have started an argument with his daughter. When Malice said she started it, the girl’s father accused the boy of lying to a cop — which could, he threatened, get him into a lot of trouble.

Ten-year-old Malice responded by laughing in the man’s face and saying either “What are you going to arrest me for?” or “Let me see your badge” — he couldn’t recall which. When he told his parents what had happened with an enormous sense of pride, they reprimanded him.

“I was so disgusted with them that I still feel it today,” he states in Pekar’s comic.

Excerpt from Harvey Pekar’s comic book “Ego & Hubris: The Michael Malice Story.” Ballantine Books, 2006.

Some version of this dynamic would occur throughout Malice’s life; his personal eternal return. First, he would encounter an unimpressive authority figure whose supposed status he refused recognize. Then, he would challenge said figure by exposing their fraudulence to their face, leaving the figure to resort to bullying. This response only served to further motivate Malice to destroy them — an inevitability that transpired time and again.

In high school, he had a creative writing teacher, Miss Powell (a pseudonym in the comic), who despised his absurd, twisted stories so much that she threatened to give his friend a poor grade if he continued to sit next to Malice in her class. War ensued, and eventually his classmates began following his cues by writing edgier stories — one of which ridiculed Miss Powell by implying she was a dominatrix.

On the final day of class, the teacher, to Malice’s immense pleasure, broke down into tears. The following semester, Miss Powell confessed to her class that Malice was evil and that she hated him. Shortly thereafter, he presented the teacher with a poster titled “Miss Powell’s Road to Madness” featuring a road leading to an asylum.

During his time at Bucknell University, Malice was shocked to learn that his professor had failed to read a pamphlet on copyright law that he assigned. Moreover, Malice discovered that he knew more about the subject than the professor, who, at one point, had to admit that he stood corrected. Following another cordial disagreement during the next class, the professor sent a letter to Malice informing him that certain tenets of his lecture were not up for discussion.

Bewildered that the professor would put such a threat into writing, Malice ultimately took the letter to the dean of the school. The matter ended with the professor agreeing to teach Malice in an independent study — anything to keep the student out of his class and thereby save himself from further humiliation in front of his students as well as censure from the dean.

Two other key events occurred during his mid-twenties that demonstrated what Malice called his “anarcho-elitist mentality.”

One day, after being summoned to his consulting firm’s office building, Malice encountered a security guard on a power trip. Although a second guard promptly worked with Malice to resolve the misunderstanding, the first guard wouldn’t let it go. Malice tried to end the interaction, but the guard persisted until Malice explained to him, “There’s a reason why some people work upstairs, and some people work the door.”

When the guard threatened to break Malice’s jaw, he relied, “Oh, really. Ha! What’s your name… Ben? We’ll see about that, Ben.”

Malice filed a complaint with a police officer, contacted the building manager, and Ben was fired.

Then came jury duty. When the judge explained that the jurists had to agree to apply the law in his courtroom as he saw fit, Malice explained that, as an anarchist, he recognized neither the judge’s authority nor his interpretation of the law.

The first case involved a woman who broke her hip when she fell in the projects and sued the housing authority. Malice explained to the attorneys that he wouldn’t be suited for the jury because he would suggest deducting any rent subsidy she receives from the award due her.

He was dismissed from the case.

In another case, when the judge told the jury how important they were, Malice asked, “If I’m more important than the attorneys, can I bill at their rate?”

The attorneys were so impressed by Malice they wanted him to be a foreman for the jury. Malice said he wouldn’t take an oath or be sworn in. Even though the attorneys suggested they could “work around that,” the case was resolved and all jurists were dismissed.

Excerpt from Harvey Pekar’s comic book “Ego & Hubris: The Michael Malice Story.” Ballantine Books, 2006.

In 1999, Malice began working as a consultant to make ends meet while pursuing creative projects during his time off. After graduating with a business degree at age 21, he didn’t quite know what to do with his life but he was determined to avoid a 9-to-5 desk job so he could focus on his writing.

One of his early endeavors involved a novel that retold biblical stories — an effort that took about two years. He also became fascinated by a country western new wave band called Rubber Rodeo. What he first envisioned as a novel transformed into a screenplay after he tracked down and interviewed members of the broken-up band.

He also took a stab at stand-up comedy “for a minute,” he told me. “I quickly understood I’m not cut out for the lifestyle, even in the unlikely event that I could develop the talent and following.”

When I asked if he always wanted to be a writer, Malice said, “God no, I wanted to be a zookeeper. … My goal was to not have an alarm clock and not ever have to interact without someone I didn’t want to, and writing provides me with that lifestyle” — a comment that indicates why he feels “Gertrude Stein also set the path for me in several ways,” despite the fact he doesn’t think her writing is “very readable.”

As he shifted between temp jobs — working as a Human Resources assistant, receptionist, tech support for Goldman Sachs, tech writer for American Express, software trainer for the board of education in Brooklyn — Malice started to earn very good money. When a long-running gig ended, he decided to take some time off to focus on the Rubber Rodeo project.

Right around this time, he decided to cut ties with his family. One evening, when he was out to dinner with his grandparents, his grandmother accused him of “denying” himself food because he was spending all of his income on books and CDs — which, according to Malice in the comic book, was

pure psychosis on her part; she had no idea — none — how I spent my money. I looked at her when she was saying this and I realized that there is absolutely nothing you can say to a person who would feel comfortable suggesting something like that, let alone a direct accusation. We got to arguing about this and she asked me if, based on my tone, I thought she was a bad grandmother. “No,” I said, “But I think you’re a bad person.”

Malice began wondering if speaking to his family gave him any pleasure whatsoever. He asked himself why he cringed every time the phone rang out of anxiety that it was a family member calling. He could no longer justify putting himself in these uncomfortable situations.

He didn’t speak to his family for three years. While he did speak to his mother on rare occasions, she wasn’t allowed to call him at home. His relationship with his father had been strained since he divorced his mother and moved in with his old girlfriend from Russia. His father eventually married a woman closer to Malice’s age than his own and insisted that the two of them become friends. When Malice said he wasn’t interested, his father told him, “Tough s—.” The relationship further deteriorated from there, with Malice concluding that there was “nothing more pathetic … than a mid-life crisis, because there is nothing more important to me than integrity.”

It would be years before he spoke to his father again, and the circumstances of their meeting — the wedding of one of Malice’s grade school friends — gave him a sense of dread. He found himself puzzling over what his father could possibly say to a son he hadn’t seen for so long.

When his father approached him — interrupting a conversation he was having, Malice noted — he said, “Let me get a look at you.” Then, “Your tie is crooked.”

After several more years of no correspondence, Malice decided he would give his father another chance — perhaps, in part, because he wanted to tell him that Pekar was writing a graphic novel about his life. When he told his father, he responded, “I know — so?”

“It was one of those moments where I’m like, Wow, you’re an asshole, and not the kind of asshole I am, you’re just like not a good person,” Malice told Fridman during a Dec. 15 episode of his podcast. “And I don’t know, or really at this point care, what the motivation, or if there was no motivation, what the visceral emotional reasoning for that [was]. But that kind of thing is something I — much later now in life — have absolutely no tolerance for.”

Since that exchange occurred over a decade and a half ago, I was curious if Malice’s relationship with his family had ever healed.

“No,” he said. “And from talking to my sister they’ve gotten worse. Very unfortunate stuff.”

‘The White Pill’ and a Warning for the West

During a discussion of totalitarianism and anarchy on a July 15, 2021 episode of Fridman’s podcast, the always-composed Malice broke down.

He was trying to explain how virtually impossible it is for most people to understand what life was like in the Soviet Union in which his family lived, or modern-day North Korea, or Germany before Hitler.

“It’s not like before Hitler came, everyone’s dancing around and having a great time,” Malice said. “Imagine what that life is like where your preference to Hitler is starving, and waiting on line hours for bread, and to have the secret police, and your friends are turning you in, and your phones are all tapped and you’re a prisoner — but to you, this is infinitely better than the alternative. These are the choices our family had to deal with.”

Then, he compared the situation to your first very bad break-up in that you can’t understand what it’s like until you experience it. But even this description failed to capture the inconceivably miserable living conditions of people at the mercy of a dictatorship.

“I remember my grandma—” he said, stopping short, unable to continue. “Um— she would talk about how, like—” he exhaled. “When you’re that hungry, all—all you’re thinking about is bread, because your brain won’t let—you know, human beings—” he wiped away a tear “—we’re evolved, we have instincts, whatever, and the mind is telling you food, food, food, food, food, food, and that there’s kids thinking this, and they’re not gonna get that food. And imagine being a parent…”

He continued:

We have no concept of what it’s like. … it’s just like, last night, here in Austin, all the places were closed and I couldn’t get my protein powder and this is the extent of my suffering when it comes to food. … There was a restaurant that I went to in Brooklyn where for some ferkakte reason they weren’t serving sashimi, they only had sushi so I had to have the rice and the carbs.

To live a life where that is the extent of your food problems as opposed to the choice is either Hitler killing you or being hungry 24-7…

My grandma told this story of how they had a close call. It was her and her brother and her mom, my great-grandma, who passed. And I think there was a helicopter overhead or something and my great-grandma jumped on top of my grandma’s brother and not my grandma. So she basically did a Sophie’s choice — my grandma’s name is Sophia — and chose the brother and this is something that she felt all her life, that her mom had chosen her brother over her.

…

It’s things like this — the fact that you and I dodged these bullets and that we can be here and be doing this and running our mouths for a living, I think about it all the time.

Malice confirmed to me that the grandmother he referred to in the interview was the same grandmother who constantly badgered him for being too skinny.

I asked if he thought the trauma she experienced in the Soviet Union ultimately made it impossible for her to have a healthy relationship with him.

“I thought so for a while and then mentioned that to my mom and she pointed out my great-grandmother, who had it even worse, wasn’t like that,” he said. “So no, that fed into it to some extent but that wasn’t the explanation.”

One might want to put too fine a point on such a connection: even though The White Pill is a history book, Malice was writing from a very personal place; it’s a tour de force of journalism filtered through his gut and from his heart. At the same time it seeks to educate Americans about the brutal realities of living in the Soviet Union, it also functions as the author’s attempt to explore how past terrors crept through generations and disrupted intimate relationships beyond repair.

Was this connection a motivating factor during the writing process?

“Yes, absolutely,” he said. “In a parallel universe I would have never left the USSR as a small child, and part of writing this book was trying to understand what that literally would have meant and felt like. Spoiler: it did not feel good.”

I’m one of the few USSR exports that works https://t.co/H3uW2z8trP

— Michael Malice (@michaelmalice) October 25, 2022

It’s a testament to the muscularity and pacing of Malice’s writing, and his discerning selection of documented details, that the book induces a feeling of imprisonment for the reader. The scenes of suffering are extreme and revolting. One passage in particular, excerpted from Victor Sebestyen’s biography of Lenin, is destined to implant itself in the reader’s mind forever:

Nursing babies have lost their voices and are no longer able to cry…A woman tries to soothe a small child lying in her lap. The child cries…For some time the mother goes on rocking it in her arms. Then suddenly she strikes it. The child screams anew. This seems to drive the woman mad. She begins to beat it furiously, her face distorted with rage. She rains blows with her fist on its little face, on its head, and at last she throws it upon the floor and kicks it with her foot. A murmur of horror rises around her. The child is lifted from the ground, curses are hurled at the mother, who, after her furious excitement has subsided, has again become herself, utterly indifferent to everything around her. Her eyes are fixed, but are apparently sightless.

Malice writes about how

Pregnant women trying to steal food were beaten to death, with their remaining children invariably starving. Children trying to feed themselves were shot as well. Digging mass graves became grueling working, and barely-living kids and the elderly were tossed alongside the dead in order to save the extra trips. Their last hours on earth would be spent slowly dying, surrounded by the corpses of their countrymen.

“Two of the more bizarre replies I receive are that I believe humans are basically good, and that I underestimate the malevolence of the enemy class,” Malice said. “This book demonstrates the contrary.”

It’s difficult to imagine how someone who’s read any of Malice’s work could reach that conclusion.

In many ways, The White Pill represents the culmination of what he has been working toward as an author. His first solely-authored book, 2014’s Dear Reader: The Unauthorized Autobiography of Kim Jong Il, is a kind of farce-played-straight that presents a first-person account of the communist leader’s life alongside the history of the country. His previous efforts as a co-writer of books for celebrities, including comedian D. L. Hughley, sharpened his ability to inhabit the skin of another person.

“I wanted people in the West to understand what the North Koreans really thought, and I wanted to do it in an entertaining pop way,” Malice wrote in a 2013 Reason article. He also visited the country — partly for research, but also because he said it “would be my best chance to see what my family had gone through before we fled to Brooklyn when I was 2 years old.”

While his second book, The New Right, doesn’t focus directly on totalitarianism, it does present the explosion of heterodox ideas that arose in opposition to the Establishment. The book is populated with radicals of many stripes who broadly despise what the neoreactionary writer Curtis Yarvin termed the Cathedral, or “journalism plus academia.” One senses Malice’s excitement over the existence of so many fellow subversives. Perhaps he was drawn to the notion of elevating those marginalized voices because when those voices are shut out or shouted down, its easier for normies to stay blue-pilled. When those normies vastly outnumber the free-thinkers, the door to totalitarianism cracks open.

His third effort, The Anarchist Handbook, is a collection of essays from famous anarchist writers, including Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, Mikhail Bakunin, Murray Rothbard, and Emma Goldman — a hero of Malice’s who plays a leading role in The White Pill. The book aims to introduce a new generation to the philosophy of anarchism, which he defines in the introduction as “nothing more than the declaration that ‘You do not speak for me.’” He further notes that “an anarchist world would still have murderers, and thieves, and evil men and woman. It simply wouldn’t put them in a position to enforce their evil on everyone else via getting elected and decreeing the law.”

It may seem obvious that Malice’s preoccupation with and contempt for totalitarianism drove him into the exact opposite direction ideologically. If a ruler can create untold suffering, then it’s logical that no ruler — literally, the definition of the word anarchy — is ideal. In The Anarchist Handbook, Malice acknowledges that anarchism “has been both a vision of a peaceful, cooperative society — and an ideology of revolutionary terror. Since the term itself … is a negation, there is a great deal of disagreement on what the positive alternative would look like. The black flag comes in many colors.”

When I floated the idea that hope for an anarchic society at any scale might be utopian, Malice corrected me.

“Anarchism is not a location, it is a relationship,” he said. “The healthy, thriving parts of any society are the anarchist elements, meaning peaceful interaction without invoking any sort of authority.”

He pointed out, for example, that it wasn’t necessary for the Catholic Church to collapse in order for Christians to regard themselves as fully Christian without having any association with Rome.

“That’s a far closer analogy of how anarchism would develop,” he said. “That there would be people running their mouths in Washington but they would be effectively impotent to do much about it.”

He continued: “Under anarchism there is no pretense that the opinions of randos should be taken seriously, in the same exact way that we don’t really hear who Canadians would prefer to win a given gubernatorial race in the US. Only democracy puts forth the demented idea that everyone has something of value to add to every conversation.”

Though Malice doesn’t vote, he did contribute money to the Biden campaign in the primary and to John Fetterman’s bid for the U.S. Senate.

“I want Washington to be more explicitly like Arkham Asylum,” he said.

— Michael Malice (@michaelmalice) November 4, 2022

When I asked if it’s absurd, in the U.S. in 2022, to hope for better politicians, Malice said: “I don’t know what ‘better’ means in this context.”

He added:

One can easily make the argument that better lawmakers prolong the suffering and leave the mechanism in place, validating it for when the worse come along. If someone wants to vote in local elections, that’s their prerogative. I think the time they spent voting could be far better spent improving lives in infinite ways, such as volunteering to help children in need or the elderly.

One would have to feel deeply nihilistic to argue with The White Pill‘s thesis: “It is possible that those of us who fight for the dignity of mankind will lose our fight. It is not possible that we must lose our fight.” However, I couldn’t help but fixate on the fact that “the Soviet Union went from being a perpetual world-dominating superpower to literal nonexistence … a forgotten chapter … a kitschy joke” because of Mikhail Gorbachev — a politician.

It seems, I told Malice, that a malevolent government was ended only because a benevolent political figure took the reins.

When I suggested I might be misunderstanding this point, Malice said, “Yes, you are misunderstanding it. But if the book wasn’t clear enough I’ll take the responsibility.”

I suggested that Gorbachev was “better” than his predecessors by every metric, although “better” might not be the most appropriate word. Does he think it’s absurd to hope for a Gorbachev-type figure who could drastically reform the federal government?

“Yes, I think that’s absurd,” he said. “A president doesn’t have the same type of leeway as the highly centralized Soviet leader did. Plus our systems are very different obviously. Imagine if George Washington became president now. I don’t think anyone can make the claim that he’d bring us back anywhere close to the era of the founders, or would drastically increase the authority of government.”

The Author Takes Refuge in Austin

In August 2021, Malice left New York City, where he had lived nearly his entire life, and moved to Austin, Texas.

“It’s been very disturbing to see what has happened to my beloved city and I couldn’t deal with it any longer,” he said in a Stu Does America interview.

He explained that his devotion to New York City had previously been so strong he wanted to die there — even if it was the result of a terrorist attack.

“Nothing Mohamed Atta did compared to what Mayor de Blasio did to New York City,” he said. “Everything that was unique and special about New York they systemically destroyed … Coming from the Soviet Union, the idea that I have to show papers in order to eat at a restaurant, to have this free exchange of my money in exchange for food, is something I find completely unconscionable. My health decisions are my own and nobody’s business but my own.”

Just bought my one-way ticket to Austin pic.twitter.com/IRjxIJxAPO

— Michael Malice (@michaelmalice) August 25, 2021

Now that he’s in Austin, a city to which a number of his friends have moved, it seems Malice has achieved the goal that he set for himself as a young man: to never interact with someone he doesn’t want to.

“I’ve finally gotten a community again,” he told me. “I hadn’t realized just how isolating New York City had become in the previous couple of years.”

By his own admission, he doesn’t really go anywhere.

“I spend way too much time with my friends sitting in my house and watching YouTube compilations of people falling down,” he said.

Although he enjoys dining at Roaring Fork and visiting the Driskill Hotel — as well as the bar Jackalope, even though he doesn’t drink — he said, “Austin doesn’t really have a lot of go-to places.”

It’s difficult to imagine Malice having too much downtime. Between hosting his own podcast, making guests appearances on a variety of other programs, and dealing deathblows to midwits on Twitter — which he said “eats up a lot of my time” — he manages to stay busy.

Recently, while reflecting on his output as an author, he said, “Each of my books is a time capsule of my life so they each mean a great deal to me in different ways. Nor have I had any flops, so each one has some sort of metric of accomplishment associated with them.”

Since The White Pill represents the latest apogee following his pattern of success as an author, one wonders where Malice goes from here.

I asked if he has a work-in-progress or plans for a new book that he could share.

“Calm down,” he said. “I just birthed this one.”