Begin with The Case for President Ye (Part I), which can be read here.

Ye walked into the church wearing the same jacket with the black boots and dark denim jeans—no mask on. All smiles. A tall, gray-haired man in a long leather jacket and jeans followed him.

Ye introduced him to me as his “homeless theologian,” Mark. Supposedly, he lives out of a car nearby. Mark carried a giant Bible and some water in an old bottle of Hawaiian Punch.

There were about ten of us waiting in the entrance for Bible study to begin—watching for the red light to turn green on the percolator.

The woman in charge of the coffee said good morning to Ye and asked him who the picture was of on his shirt.

“It’s my mom when she was a child,” he said.

He poured himself a cup of coffee and asked me, “What were the elements of the interview yesterday that brought you to life?”

“The idea of collaboration,” I said. “I think that’s one of your strongest gifts… listening to different people.”

No one at the church treated Ye any different than anyone else. There were no pictures. No surprised looks. All hellos and good mornings and small talk. Ye seemed at home and comfortable. It was low-key. I realized I had yet to see his fame really interact with the world, and for that, I was grateful. I think something sparks in our eyes when we have to interact with cameras and flashing lights. Even if we try to suppress it, the cameras manipulate our existence. I think that might be why Ye has chosen to wear the mask so much in public. It creates a barrier between him and the cameras. It creates a bold image and reduces him to his words. It’s an act of minimalism, but also, probably, an act of protection—the jacket, the boots, the mask, they are a form of armor.

At Bible study, Ye and I sat at a folding table facing the pastor’s brother, who stood at a podium made of carved tree limbs. There were mostly older gentlemen in attendance, plus some women with bone-white hair.

Ye looked at the ceiling and asked how they might be able to bring more natural light inside—as if he wanted to cut a giant hole in the ceiling to let the sun in.

Behind Ye, right above his head, was a JFK quote stenciled on the wall: “The rights of man come not from the generosity of the state, but from the hand of God.”

We opened to James 5.

“You can’t worship things,” the pastor’s brother said. “Everything you’ve been saving up and working for gets left for someone else… You have heard of the endurance of Job… Job went through more than anybody…but he was capable of going through more than anybody… He went from being a billionaire to a trillionaire… He lost everything. And then, at the time, his wife would say things like, ‘You know, why don’t you just curse God and die?’ Why are you putting up with this?’”

Ye listened, never speaking—but there was a pressure in the room when clear references were drawn between Job and Ye—though I think we can all relate to Job in some shape; however relative the challenges and grief may be. But I was certainly sitting next to one of the only men on Earth who could resonate with something like “losing billions.”

Eventually, the sound of the piano wandered through the wall. Service was beginning. Music echoed through the high ceilings—the exposed wood beams above us like the bones of the church.

As we took our seats in the pews, Ye said, “I had his epiphany, excavating my thoughts, ideas, and memories. Mark says, ‘we’re going to have to run a perfect campaign in order to win.’”

Ye’s careful to say he’s “running” for office because the proper paperwork has yet to be filed.

“The king don’t drink,” Ye continued. “No fornicating. No pornography. But also, this thing where I’m saying ‘love, love, love.’ I just texted Elon right now and said we need to have a conversation on camera about free speech. You know, he can say something about not wanting to commit suicide [as he exposes rampant speech suppression on Twitter and fears retribution]. And what I’m saying to him is, ‘love everyone. The Jews need to forgive Hitler and stop forcing your pain on other people.’”

“The big problem with trying to control any narrative out there is that Satan’s in charge of it all,” the pastor’s brother said. “He controls Twitter, he controls radio.”

I’m reminded of Paul Harvey’s “If I Were the Devil.”

“Elon’s atheist,” Ye said.

“But Elon’s a sensible guy,” the man said.

“He just kicked me off Twitter!” Ye said. “My whole thought was the swastika inside the Star of David is, ‘everyone, let’s hug it out.’”

Ye, Mark, and I watched a young man named Michael sing praise songs with an acoustic guitar. The piano accompanied him.

After his song, Michael walked to the edge of the stage and said he wanted to share his testimony. People leaned forward.

“My dad, unfortunately, killed my mom when I was six years old,” he said. The church grew even quieter. “Growing up, I’d ask God, ‘why do I have to endure this pain?’ I was struggling with love and forgiveness, but God said, ‘you need to forgive your dad.’ ‘How am I going to forgive my dad?’ I said. I’d rather see him die. I’d rather him suffer. But God said, ‘I want you to write to him.’”

His father had been in prison for the murder.

“If I can forgive you, God,” Michael said, “why can’t I forgive him?”

Michael decided to finally extend forgiveness.

It was interesting to watch people not talk about Ye’s recent Info Wars interview but allow it to move them in a way that it seemed like they needed to express this outsized forgiveness. People kept openly embracing the idea of loving someone who has caused them direct physical or emotional harm.

The pastor wore a studded belt, had multiple rings on his fingers, and had curly hair. He told us he hadn’t prepared a sermon and that, instead, he would speak to us directly from his heart. He paced the stage, speaking freely about worship and love, and threw in some politics as if he knew he had the ear of a potential candidate.

“Michael was talking about forgiveness,” the pastor said. “I’m so glad he brought that up because that is a huge stumbling block for so many Christians.”

He ended the sermon by speaking about his own challenge to strive for forgiveness. Another one of his brothers, one of the triplets, had passed away recently from an overdose. The pastor found his brother’s body. The rigor mortis had already set in, and the pastor sat beside the body weeping. It was a cruel and terrible scene to imagine—but the pastor, I believe, wanted to place this image in our minds and then extend love and forgiveness. This is not unique from what Ye had been saying recently about loving everyone. But it certainly seemed like he’d inspired a new wave of it.

Toward the end of the sermon, the pastor walked down from the stage and stood right before us and said, “The Apostle Paul said, ‘The worst thing is the wasted life.’” He told everyone to love and to act boldly.

After the service, Ye and the pastor played pool in the room where we had Bible study. A poster of Ronald Reagan watched them play. It reminded me that the day before when Ye overheard the word Pagan come up in conversation, he paused and said, “Ronald Pagan.”

As we all got ready to leave the church, I figured I was going home. I thought this would be a pretty good end to the story. Seeing Ye experience this reciprocal love and forgiveness. Experiencing the calmness from within the church. Leaving with a sense of hope. But when I went to say goodbye to Ye and thanked him for having me, he said I should hop in the car with him.

Ye put on the black mask before we walked into the parking lot. A fan waited outside for a photo.

I sat in the back of the car as me and his friend watched Ye stand with the fan for a minute.

“Where are we headed?” I asked his friend in the driver’s seat.

“I’m not sure,” he said. “It’s all unplanned for me.”

“You from here?” I asked.

“Chicago,” he said.

“You like it out here?”

“Absolutely,” he said. “Southern California is kissed by the Gods.”

When Ye got in the car, he said, “I like that pastor. He’s my favorite pastor.”

“What makes him your favorite pastor?” I asked.

“He’s me as a pastor,” he said. “But like a seventy-year-old version.”

“I was curious what churches were like out here,” I said.

“Well, now you know,” he said. “They’re not like that!” He laughed. “This is the only church like this.”

Lauryn Hill sang “The Sweetest Thing” on the stereo. It seemed like the faster the car went, the louder the music got. Then Curtis Mayfield’s “The Making of You” came on. It must’ve reminded Ye of his song “The Joy” off Watch the Throne, which samples it—so he put on Watch the Throne and started rapping along to “The Joy.”

I did not know where the car was going. Nor did I care. I never saw a Ye concert. And I never imagined the first time I’d see Ye play his own music would be in the backseat of his car whipping around LA.

When the song ended, he started to play Watch the Throne from the beginning.

“I only wanna hear the songs that we never hear,” he said.

He played “Lift Off” with JAY-Z and Beyonce, and as he turned up the volume even more, the car accelerated, and our backs pressed against the seats like a jet taking off. I thought of the images that accompanied Watch the Throne. Ye and Jay smiling in the Otis video. The two of them playing “Ni**as in Paris” 12 times in a row at a show in Paris.

After a handful of Throne songs, Ye turned down the music and asked what I thought about Bible study.

“I focus too much on what I have or don’t have sometimes… I wrote down the phrase ‘reject materialism’ when I was listening to the guy talk. But I don’t fully think that’s what I believe, actually. I personally don’t really want things. But I want others to be able to get what they want, if they want it and can afford it. I think what I really took away from it is to not be beholden to materialism. The things we want in life really don’t mean anything in the end.”

As a former furniture mover for an auction gallery who spent ten years cleaning out dead people’s homes, I can’t tell you how true this is.

Ye mentioned that he’s still working on the Donda School—named after his late mother.

“I want to embrace children on the spectrum,” he said.

“I think children on the spectrum are lightyears ahead of quote-unquote normal people,” I said.

He would later start telling people that he believed he wasn’t bipolar but, in fact, on the spectrum. And that this was his true superpower.

The scenery changed from highway to hills, and the houses got bigger.

“Did Elon get back to you about the free speech thing?” I asked.

“Nope,” he said.

“You know he’s like half-Chinese, right?” Ye asked.

“I feel like he’s not even a human anymore. I think he put the Neuralink in his brain years ago,” I said. “Look, I love what he’s doing with Twitter, mostly. He’s working to rid the platform of child porn and sex trafficking. And that’s amazing. We need that. But I also don’t agree with what he’s doing to you or Alex Jones, and how I think he’s viewing free speech based on subjectivity.”

“I’ve lost millions of dollars for a tweet,” Ye said.

“I wish he could’ve said to you, ‘I don’t like his tweet, but it’s fine. Let him say what he wants, and we can all have an open discussion. But he said he won’t restore Alex Jones because of personal feelings. He got rid of you because of personal feelings… He said he wanted to punch you.”

“Who made him the judge?” Ye asked.

“Twitter is his toy,” I said.

“I cracked the code with the ‘love Hitler’ thing,” Ye said.

“Did you know you would go on Info Wars and say that or was it just off the top?” I asked.

“I honestly forgot,” he said, laughing.

He’d been talking to Adin Ross that morning—a popular twitch streamer. He and Ye went back and forth about the Hitler comments.

Ye said he told Adin, “Take Balenciaga. Take Hitler. Take whatever the conversations and arguments are about—then take water away for one day and see what the conversation and arguments are about. Take water away for two days, three days… then see what we’re all arguing about… I want to start fasting to prepare for that.”

*

We drove up to a giant gate that slowly opened. A man was waiting to open the car door. When we got out, I thought I heard the ocean.

The driver said goodbye to us both, and I followed Ye into the building, up two flights of stairs, and into a room with a giant TV and a small table with two chairs. He flipped a switch, and the shades drew up along the wall of windows. The ocean was below. This was my first time seeing the Pacific.

“Is this your spot?” I asked.

“It’s a hotel,” he said.

We sat at the small table by the window. He put his mask on the table beside my notebook.

“How do we win?” he asked about his campaign—the sound of the waves crashing just below.

I told him I thought that everything he’s doing right now with the “I love Hitler” stuff is a form of radical destruction to usher in radical love. Unity by way of forgiveness. Referencing what I had told him the day before about burning the simulation. The current simulation operates on mass division. But as he said in the car, he cracked the code. Extend love to even the worst, and it kind of forces the conversation to shift towards forgiveness and unity—not holding onto generational pain. We live in a world that perpetuates references to pain—victimhood is a currency.

“By showing love to one of the worst humans in history, you are shattering the concept of resentment and hate,” I said. “And it’s controversial… If everyone had been paying close enough attention over the years, they wouldn’t have been so surprised at you saying you love Hitler and the Jews… I hate to even bring this up,” I said. “But you are the dude who was going to put the face of the doctor that killed your mother on a cover of your album—because you had said years ago that you forgave him.”

As I said that, I realized his mother’s baby photo was staring at me from his shirt.

He responded with a surprised look—as if he hadn’t considered that in a while.

“So, this, to me,” I said. “Seems like an evolution of that. You’re also the dude who wore a Confederate flag during the Yeezus era—to reclaim what many see as a symbol of hate. But, I think you do this all out of an opportunity to spread love—as controversial as it comes off to the public. Like, look, my mom is not happy that I’m here. She doesn’t like you right now. A lot of my friends are tapping out. But I don’t think they get it. I know many people’s gut reaction is to recoil from what you’re saying—even though I’m fairly certain it’s rooted in love. It’s radical. It’s hard to digest. But if we are going to move forward from these last few years of terrible division, it might be the only true path forward. To forgive one another. To forgive the past. To forgive everything that went wrong… and start fresh. It seems impossible, but something about you saying something as ridiculous as ‘I love Hitler,’ I think it could shatter the concept of generational pain and resentment. I find the act of forgiveness and total love to be contagious.”

I realized after looking at the photo of his mom on his shirt, that I, too, was raised by my own Donda. Great mothers are the ones who know how to make their children feel like they have the power to change the world.

“How is unity possible?” he asked. It felt like he’d flipped the interview on me long before I even realized it.

I mentioned something I had brought up in the conversation with him the day before.

“Remember how you learned from watching Bono sing on stage, around the time of making Graduation, when you guys were on tour, to condense your verses into something bolder and simpler, so that massive stadium audiences could sing easily in unison? The way you saw them singing along with U2… I feel like you can apply that to politics. I mean, yeah, there’s a radical disruption happening right now which I enjoy, and I think from this destruction, a radical love can emerge. People are focusing on the radical destruction part. You said, ‘I love Hitler,’ but you also said, “I love Jews.”

(Yesterday, when I brought this idea up, I told him “I want to think this is all coming from a Christ-like place … and maybe a little Andy Kaufman, too.” To which he responded: “People will say that’s a technique… That’s like how Bruce Lee has different techniques. Yes, that’s bit of my approach…. We Alex Jones-ed Alex Jones. We put Andy Kaufman in an old folks home.”)

“It feels like you’re throwing grenades everywhere you go,” I said. “But we need that unity, that stadium-singing-in-unison unity. You gotta plant flowers after you cause some destruction.”

I told him how the last few years exposed just how much the system finds nourishment in human suffering. That, personally, it never felt grimmer in my life—despite the joys of my children, the love of my wife—it was an emotionally disfiguring few years not just for me but for the world.

He asked me why the last few years were that hard—and I could tell he wanted specifics. I explained everything from watching the college institution rot from within to writing a poem that upset many friends during the first lockdown summer with the George Floyd riots. I told him how I pretty much always just avoided talking about politics. I honestly don’t like causing friction, but watching David Dorn get shot in the head during a live stream of a pawn shop getting looted at one of the riots was one of a handful of images that snapped my brain. He hadn’t heard of David Dorn, so I described that scenario in detail and how nightmarish it was to see someone bleed out of their brain on a sidewalk on a livestream, as a city burned, as a store was looted, as people ran by, as a young man screamed for help, and then the way it was seeing the life extinguish from a man’s eyes.

We sat in silence for a moment as the image of Dorn cast a shadow over our thoughts.

“The other thing I think about now when it comes to you saying you want to rewrite the constitution is the idea of blasphemy laws that could potentially be a part of it,” I said. “I understand that we are morally bankrupt in this country. We could point to any number of things going wrong, but—I worry that such laws might suppress free expression. And if we suppress that, if we create these laws where we redefine ‘obscene,’ I wonder if a young Ye could even exist in that world?”

I worry about how it might affect free expression.

“We gotta look at what the Bible says,” he said.

I considered how that interpretation would work. I do understand the need for morality to be placed back in the soul of the nation (to quote Joe Biden). But I think the two greatest and most American art forms happen to be the Novel and Rap. And they are vessels for true expression—as well as subversion—and love, God, and free will.

“So, when it comes to unison,” I said, “It might be good to build a team with a range of opinions.” I mentioned how I was impressed the other day by a democrat like Ro Khanna speaking up about Twitter censorship. (Something we learned through Matt Taibbi’s first installment of the Twitter Files.) The difference of opinions should only help build the immune system of the future campaign’s ideas. I told Ye he doesn’t need to agree with these people or adopt their beliefs, but the healthy disagreements might embolden his own—plus be good for a nation looking to him for hope.

“It’s the light movement,” Ye said. “All these bad things happen in the dark.” He referenced sex addiction and human trafficking… We have the will and the information to change it,” Ye said.

Eventually, the conversation switched to Trump.

“Trump was fun in office,” I said. “He did many good things that no one cared about.” I listed off funding HBCUs, signing Right to Try, the Abraham Accords. “And I liked his plan to help black communities. Remember when [Ice] Cube got in trouble for talking to Trump about it? Then Biden tried to steal Cube and do his own deal?”

“Steal what?” Ye asked.

“When Cube talked to Trump about the Gold Plan?” I said.

“The Platinum Plan,” Ye said, correcting me. “You know how I know it’s called Platinum?” he asked.

“Music?” I asked—thinking about records going platinum or gold.

“No,” he said. “Why else do you think I might know it’s called the Platinum Plan?” he asked, getting more serious.

I spaced and said I didn’t know.

“I named it,” Ye said. “They gonna put me in jail for saying that? I gave it to Jared [Kushner]. I gave Jared [the book] Powernomics.”

“You gave that to him? I thought he gave that to you?” I asked. I’d been thinking of this recently when he said he never read books in another interview but remembered him once saying he loved the book Powernomics.

“I don’t fully trust Kushner,” I said. “But I don’t know him like that. I do love the idea of world peace, and the Abraham Accords were his thing. I know people might say he only did it for money, blah blah blah, but I honestly don’t care. If you can broker peace between nations that have been at war forever, let’s make it happen. On a personal level, I don’t trust him because he hired someone who was a really terrible person to me. A former editor. I believe they were also good friends. So, I probably shouldn’t make Kushner guilty by association, but this dude was an abomination—and Trump pardoned him… Do you think about pardoning people?”

“I need the information,” he said.

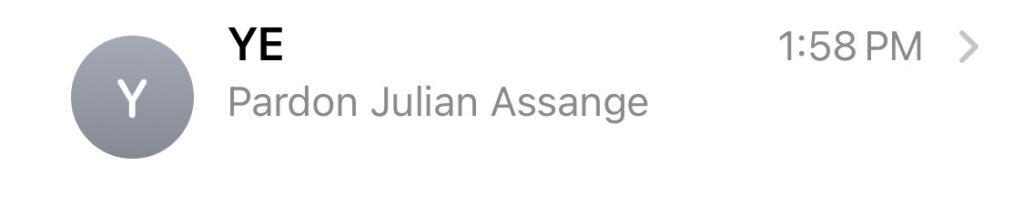

“I would recommend looking into Julian Assange,” I said. “People were really not happy with Trump and his pardons because a lot of us really wanted to see Assange pardoned.”

“Can you text me that?” Ye asked.

“Look, Lil Wayne is one of my favorite rappers of all time,” I said. “I was stoked that Trump pardoned him, but he should have also pardoned Assange.”

“What [the pastor] was saying about the Supreme Court is super neat,” Ye said.

“Have you thought about that kind of stuff, like, who would you nominate?” I asked.

“I need to get good advice.”

“As someone who’s heard politicians answer everything with pre-packaged soundbites, it is kind of nice to hear someone say,’ I don’t know,’” I said. “But… I’m going to be straight up and say, sometimes I ask myself if I have Stockholm Syndrome with you and my fandom. Like, am I just so stuck in defending Ye that I’m at a point now where I’m stuck in a defense pattern? I truly believe I’m seeing something that not many others are seeing. I’ve heard you say you’d hire people with the best answers. And I think that’s a genuine answer. Unlike a politician, you know, politicians will give you some prepackaged answers. Look at Twisted Fantasy. You had Justin Vernon and Rick Ross in a room together and gave us something like Monster. You take people from all these different places and bring them together to make something that’s still true to you, but it’s also completely new. Strong collaboration is the key to a great presidency.”

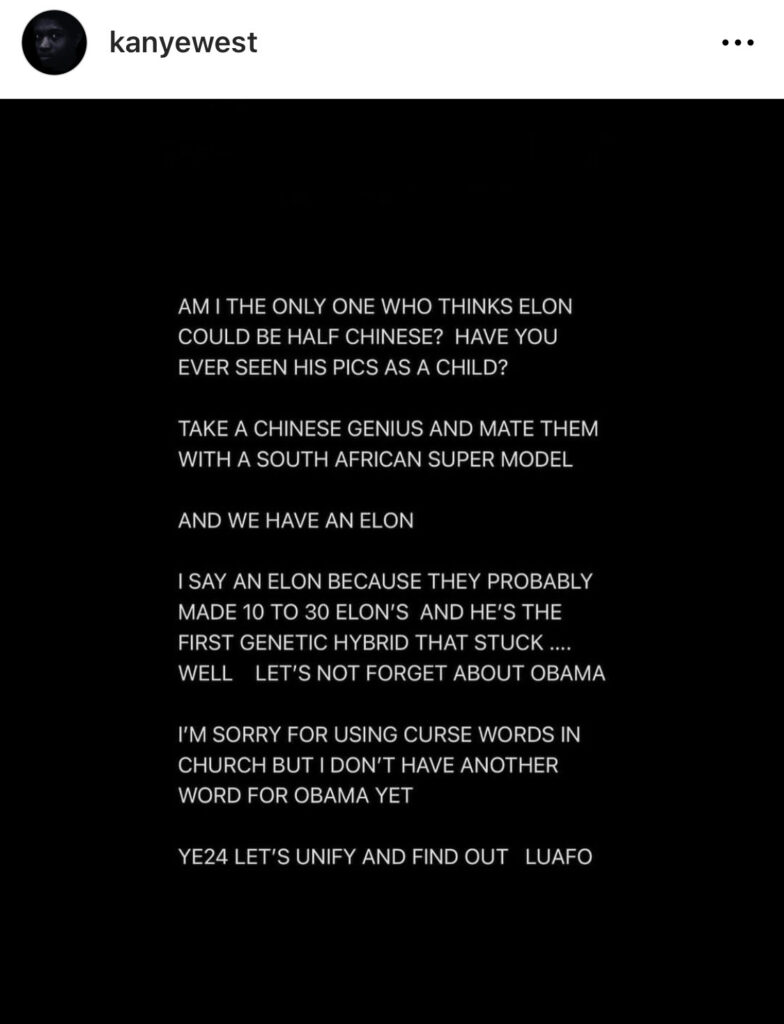

Moments later, he was back on the idea of Elon being half-Chinese.

“I’m really on this Elon’s Chinese thing,” he said, looking at his phone.

“I wish you were on Twitter right now to say something,” I said.

“I know, right, because there’s no other place to say it,” he paused— “Oh, wait, I can say it on Instagram,” he said.

He started typing on his phone.

Minutes later, he read aloud from his phone. “Am I the only one who thinks Elon could be half-Chinese? Have you ever seen his pics as a kid? Take a Chinese genius and mate that with a South African supermodel and we have an Elon. I say an Elon because they probably made 10 to 30 of them.”

We laughed.

“Can I call him a genetic mutation?” he asked.

“That… or a hybrid,” I said.

“Yeah, genetic hybrid,” he said and kept typing.

Now he spoke as he typed.

“Future President of the United States, Ye, claims, no… questions, whether or not Elon and Obama were made in laboratories… On JAY-Z’s birthday.”

Once he roped JAY-Z into it, I told him he might as well bring Zuckerberg into this, too, since Instagram is his platform.

“Uses Mark Zuckerberg’s platform to incite an investigation,” Ye said, still typing.

“Now you’re talking like a President,” I said.

“Would you use the phrase ‘genetically created?’” he asked. “How would you word it?”

“Lab made? Then it sounds like COVID,” I said.

By the end of this brainstorming session, we had successfully pulled in JAY Z, Elon Musk, Mark Zuckerberg, Balenciaga, Obama, China, and South African supermodels.

“It’s like the theory of everything,” I said.

“I call this the theory of everything,” Ye said, including that in the post too.

“Problem solved,” I said.

Then he added, “problem solved.”

We laughed like two kids watching cartoons.

“Do you hear from JAY-Z through all this?”

He didn’t look up from his phone and said, “no.”

“That’s too bad,” I said.

He added “Unify and find out” to the end of the post. I saw that as the antithesis to what Elon tweeted after booting Ye from Twitter: “FAFO,” or Fuck around and find out.

Then I heard the sound of a screenshot from his phone.

“This is how it happens,” he said with a big smile.

“You just created jobs for some people. Someone somewhere is going to write an article about this, and they’re gonna get paid like 50 dollars,” I said.

“This is what happens when I can’t be on Twitter for three days,” he said, laughing.

Later, I will search for articles about this Instagram post and find multiple pieces. The Instagram post, by that point, will have had over a million and a half likes.

One of Ye’s producers, John Cunningham, arrived with a backpack filled with a computer, speaker, and microphone. Cunningham was good friends with, and a producer for, XXXTENTACION before the rapper’s unfortunate death.

Ye asked John to loop a sample from Donny Hathaway’s “Someday We’ll All Be Free.”

Ye and John hardly had to communicate more than a few words to understand exactly what had to be done. Within a few minutes, John is cutting the loop and tweaking it so that Ye can start singing new ideas over the track. We listened to the track for a while. Ye freestyled ideas.

“Listening to loops made me successful,” he said. “Repetition is important, you hear something new each time.”

Nick Fuentes dropped by, and the two talked about how they couldn’t believe SNL didn’t do a sketch about the Alex Jones interview.

“I think they did that deliberately,” Nick said. “They did mention you on Weekend Update, though.”

“I’m not easy to imitate,” Ye had told me earlier in the day. “I don’t have a DMX voice.”

He must’ve watched parts of SNL last night because he expressed how happy he was that the host, Keke Palmer, proudly showed off her pregnancy to the audience.

“That’s positive,” he said.

Ye put on Star Wars: A New Hope as he paced around the room, writing lyrics on his phone and humming along to the track. He simultaneously wrote lyrics, recorded vocals, discussed political strategy with Nick, texted with his ex-wife Kim Kardashian about his son’s upcoming birthday, played Mancala, tweaked frequencies on the drums, and took business calls while also musing on the mechanics of the sliding doors in the Death Star. He was a blur. He moved around so much it appeared cubist. This is how he thrives. Everything at once or nothing at all—somehow constantly battling ideas of maximalism and minimalism. The mask and the name change are a reduction. But the need to ascend music, become president and change the world—at maximum.

The man has a vision for America, like he has a vision for music and design. I think he should be taken more seriously than most will allow themselves to. Yes—perhaps it is a stunt—but not in the typical celebrity way where the façade of fame and name recognition garners a few votes, and then they write a tell-all one day about their “run” for office. No—this is more like Evel Knievel’s son Robbie jumping over the grand canyon on a motorcycle. It might appear insane and dangerous to most. But Ye clearly sees himself on the other side of the canyon. Free—if even somewhat battered from the jump—but the damage is nothing compared to proving that humans are capable of wild achievements. It’s, for sure, part spectacle. But what isn’t these days? There’s an inspiration to the jump that will endure—just like men on the moon or, as Ye might say, poppin’ “a wheelie on the zeitgeist.”

He and John finished the song in about an hour. Ye recorded the bars in just a few takes. He ended the song with an audio clip from the Alex Jones interview.

“You like the uniforms, but that’s about it?” Jones says. The next line was, “No, there’s a lot of things that I loooove about Hitlerrrrr.”

He listened to the Info Wars sample over the Hathaway loop for a few minutes, thought about it, then told John to cut the “about Hitler—then loop only “that I love, that I love, that I love…” It seemed like a way of letting the audience in on the idea behind the phrase. It’s not about Hitler. It’s about love.

Then Ye asked John to loop up a vocal from a previous song of his where he sings, “This is my eternal soul” on God Is from the album Jesus is King. They got the loop just right, and Ye told John to add “piano and chords to define the chord change…”

Ye’s known for holding massive listening parties with fans to show off sometimes unfinished and sometimes finished songs. I think it’s to gauge reactions. Watching for what moves the crowd. It’s a lot like how he keeps speaking openly about his ideas for the country, understanding some ideas need new information to be refined, and then tweaking his outlook. Everything is a listening party.

This new song played for a while as the Death Star was destroyed on the TV.

Eventually, it’s nearly 9 pm. Ye put on the jacket and the boots and grabbed his mask.

“Alright, it’s time to wrap this up,” he said. We all got up to leave.

“Not you two,” he said to John and me.

He looked at me and said, “you’re going to write the lyrics for the open spots in this song.” There were specific syllables and phrasings to work with. He told me to think about what was said in Bible study that morning—about the key to Heaven. About feeling like a champion. About the beauty of life. Love in place of hate. Glory. Fearlessness. Boldness.

I think he knew this was all an out-of-body experience for me, and he probably wanted to try and further unlock those emotions on a song that sounds like the out-of-body experience of entering the Kingdom of Heaven—about the immortality of the soul.

And just like that, I was caught in the orbit of his collaborations.

Ye and Nick left. John played the song on repeat.

There is the sound of a voice exclaiming like a lightning bolt over a sample of Rev. James Cleveland and the Southern California Community Choir.

“This is my eternal soul,” Ye’s voice sang on loop through the room on high. After about twenty minutes, John packed up and left, and I’m writing down every word that comes to mind. Attempting to organize it into something that would resonate.

I was alone in the room. The sun had set. Doors open to the ocean. It started to rain, and I thought about something my taxi driver told me. The droughts are so bad in LA that when it rains, “everybody’s happy. They open their windows and open their hands and catch the rain.”

So, I just sat there with my notebook, waiting in Ye’s version of the Oval Office, hovering over the Pacific, thinking of Heaven and how we’re carried through life on fate, free will, risk, eternity, coincidence, and blessings, and joy—trying to think of the best words we can all sing together in harmony.