On our first night in Austin, my wife saw a homeless woman shit on the sidewalk in front of the Voodoo Room. When the woman was done, she helped someone direct their car into a parking space.

I appreciate this combination of depravity and altruism.

The homelessness is one of the first things you notice when driving through downtown Austin. It’s not like I’m shocked at the sight of it. We lived in New York City for years. We’d ride the subway with strange men talking about decapitating us and wait outside restaurants where men and women in cardboard houses smelled like rotting flesh. But the people living on the streets of Austin have a certain type of aggression that’s unique.

I liked watching bridal parties ride those “bar bikes” down 6th St. in the morning as the homeless peeled themselves off the sidewalk and chased after them as the women drank beer and listened to Drake and peddled at maybe two miles per hour.

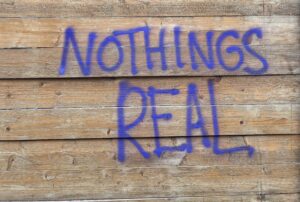

Austin inhabits that absurd disparity between the childlike joy of tourists and the anguish of drug addicts in their shrines of needles and piss bottles. I saw a lot of young women in sundresses on their way to brunch hopping over addicts in sleeping bags. Somewhere in there is the death of the American dream.

My first three Lyft drivers in Austin were Desmond Tutu’s grandson, a guy nicknamed Pigs Feet, and an old vampire with bad hearing who kept mistaking the word “bats” for “rats.”

You can gauge the mood of a city through the discussions you have with the local drivers. Everyone feels bad for the homeless. Everyone also says that it’s better now than it was six months ago. From what I could tell, the worst of it was gathered around the Vulcan or Joe Rogan’s new comedy club, The Comedy Mothership, both on 6th St. There were a few shelters nearby that were supposedly doing a better job at helping people than they were a few months ago.

We had tickets to see a “roast battle” at the Comedy Mothership. Pairs of comedians went on stage with last minute jokes written on their hands. I think one of the comedians judging the battle was our Lyft driver the night before. I remember him pretty well because he had that kind of scraggly beard an American grows when they join ISIS.

It was my first time going to a comedy show where they held your phone hostage in one of those locked Yondr bags. The entire crowd was fully engaged. No one held a phone up in front of you to take pictures for social media. No one recorded material that a comic was just trying out. It affords the comics freedom to experiment without fear of their unpolished clips going viral. We were isolated from the outside world and technology. I’d forgotten what it was like to sit in an audience whose attention was devoted to the stage.

The final roast that night was between an Asian dude with a mullet and a white kid with a cabbage patch face. The cabbage patch kid destroyed. (We were with some of our friends who work for Minds and we decided to hire the cabbage patch kid to perform a short set at the Minds Fest at the Vulcan later that weekend.)

It was good to see raw, unhinged comedy flourish. I have good friends who fled Austin years ago. One of them used to perform improv. At one point, she broke into a Hispanic character on stage and her team’s coach told her she wasn’t allowed to do it because it was “offensive.” She was confused—especially because she happened to be Puerto Rican.

When I talk to them about Austin, they can’t imagine the city ever turning around. But I think it can. My grandfather was a cop in New York City in the ‘70s. His stories from that time sound apocalyptic. Dead bodies every day. Fires. Drugs. Degeneracy. But at the same time, a counterculture was beginning to take root. Artists were moving into the dilapidated areas. Those conditions gave birth to hip-hop. I think of the way the old school tattoo artists like Thom DeVita moved into the sections of the Bowery that looked bombed-out—and eventually turned it into a vibrant hub where the bathroom inside of CBGB’s looked clean compared to what the Bowery used to look like. The night of the Minds Fest, right as the comedian took the stage, we realized that one of the guys working the door at the Vulcan was the Asian dude with the mullet. It felt like we inadvertently extended the roast.

One couple started to mock the comedian onstage.

“I hope you kill each other,” he said. He looked them both calmly in the eyes and said “murder suicide,” as if he’d just placed an order at Starbucks.

There’s a giant glass fang on the Colorado River overlooking the bridge where a million bats live. This is the Google building. It’s a dystopian sight. The tech giant built their kingdom into the sky as addicts and tourists stumble through the gutters below.

It also seems fitting that they’d want to build their fortress in a city where people were celebrating free speech in rooms isolated from their censors.

The war between big tech and free speech has been waged plenty in the digital world. In Austin, however, you can see the clear battle lines where Google erected their tower, and the Mothership has landed just three-minutes down the road. On one side you have Google’s tentacles—and on the other you have the clowns.

I think comedy will save Austin and it will reverberate throughout the country. I kept running into comedians from the Mothership working at restaurants around town. There’s a hunger to succeed here that’s admirable. My psychotic optimism might be so bad that I have faith in seeing the lady who shit in the middle of the sidewalk eventually doing a solid ten-minute set on stage at The Mothership. I imagine that happening before Google releases its chokehold on our ability to express ourselves freely online.

Austin has its problems. All cities do. But I like it here. There’s something about not feeling completely safe that can make for good comedy. It’s good for the audience and it’s good for the comedian. We can band together and laugh at the absurd—in the shadow of the Google building. It’s like how the jesters used to subvert the kingdom.

Despite the amount of trash cans I saw on fire in Austin, the city gave me hope. The clowns have invaded, and I think they’re here to save us.